Claiming a “Quranic miracle”, Islamic apologetics has highlighted a curious theme in the Quran: the existence of a “barrier” between two seas, one saltwater and the other freshwater. However, a closer examination of the verses that mention this “barrier” suggests new understandings of the probable location they describe, with indications pointing to regions far removed from Mecca.

This short article by Odon Lafontaine attempts to make sense of the verses referring to these two seas and their barrier. It has also been published on his Academia page and can be downloaded as a PDF file.

(© Israel Bardugo, reproduced here under the fair use principle for educational and informational purposes)

Some Islamic apologists, such as Zakir Naik[1] and Maurice Bucaille[2], claim verses Q25:53 and 55:19-20 as evidence of a “Quranic miracle”, asserting that they describe a physical phenomenon that would have been impossible for people to perceive, let alone conceive, in the 7th century: the differences in density between fresh and salt water. In certain places, these differences can create the appearance of a distinct separation where the two meet, such as at the mouths of the Nile or the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

Q55:19-20 – “(19) He [God] released the two seas[3], meeting; (20) between them is a barrier [so] neither of them transgresses.”

Q25:53 – “And it is he [God] who has released [simultaneously] the two seas, one fresh and sweet and one salty and bitter, and he placed between them a barrier and prohibiting partition [ḥij’ran maḥjūran, “forbidden partition”].”

It could be noted that the phenomenon of freshwater meeting saltwater has been well known for as long as people have sailed in these areas—no “Quranic miracle” is needed to recognize this. Moreover, the text makes no mention of differences in density between fresh and salt water. It mentions their mixing (Q55:19 could also be translated as “He merged the two seas mutually encountering”[4]). There is also no mention of the meeting of salt seas, as some Muslim apologists claim the verse would refer to. A much simpler interpretation comes to mind : the verses describe a saltwater sea located near a freshwater sea (not a river like the Nile), separated by dry land (the “barrier”) yet connected by rivers, allowing the saltwater and freshwater seas to meet.

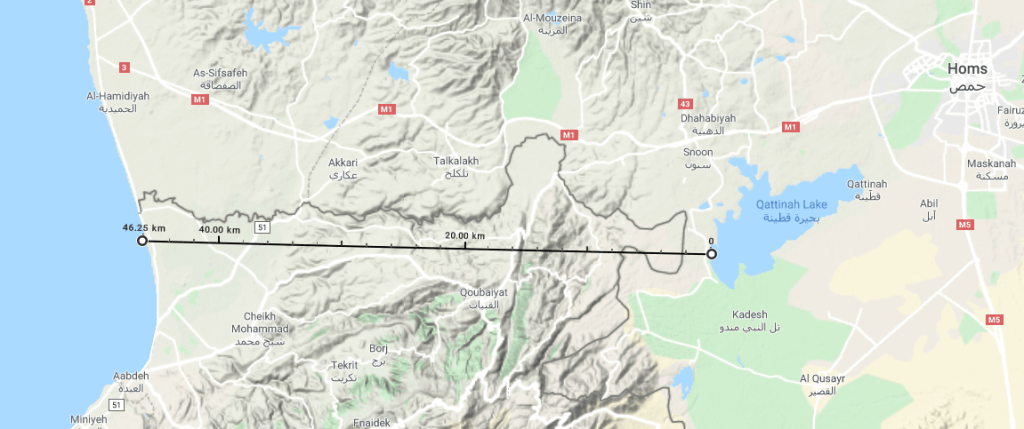

Such configurations existed in the 7th-cent. Middle East, as in Syria with Lake Homs (also known as Lake Qattinah), located about fifty kilometers from the Mediterranean Sea.

(Image generated with Google Maps, reproduced here under the fair use principle for educational and informational purposes)

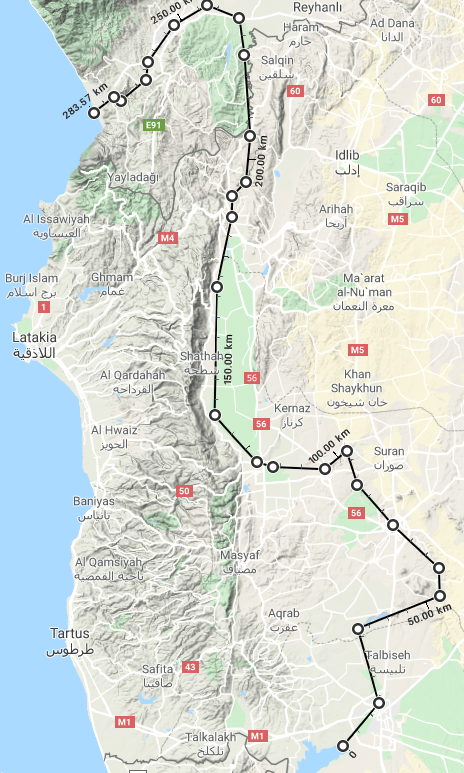

In Palestina (soon to be Jund Filastin with the Arab conquest), there is the Sea of Galilee (also known as Lake Tiberias), located about 40 km from the Mediterranean Sea and around 100 km from the Dead Sea.

(Image generated with Google Maps, reproduced here under the fair use principle for educational and informational purposes)

Both lakes feed rivers that flow into saltwater seas without the saltwater flowing back and “salinating” them (the Orontes for Lake Homs, which flows into the Mediterranean in northern Syria, and the Jordan for Lake Tiberias, which flows into the Dead Sea, a saltwater lake, in the south). This could be understood as the “barrier” and the “prohibiting partition” referred to in the Quran. There is no need to invoke physical phenomena related to differences in density between saline and freshwater, or waters of varying salinity levels, which are not mentioned in the text.

Image generated with Google Maps, reproduced here under the fair use principle for educational and informational purposes

Image generated with Google Maps, reproduced here under the fair use principle for educational and informational purposes

However, given that other verses (Q35:12; 55:22[5]) specify that the seas in question each produce “tender meat” fit for eating and ornaments (shells, pearls, corals)[6], it seems unlikely that the Dead Sea, which is completely barren, is being referenced.

To our knowledge, Lake Homs and the Mediterranean Sea, as well as the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea, are the only examples of a close configuration of freshwater and saltwater bodies in the 7th-century Middle East, as the Quran is thought to reference. Other lakes exist in Iraq and Syria, but they do not fit the Quran’s description. For example, there is the salt lake of Sawa, an enclosed lake fed underground by the Euphrates, but without the river flowing through it. Could this be the “prohibiting partition” and “barrier” mentioned in Q25:53 and 55:20? In any case, this salt lake is not visibly connected to any sea of “sweet, palatable for drinking” water. One should also mention Lake Jabbul (also known as Sabkhat al-Jabbul), a large seasonal saltwater lake in northern Syria, southeast of Aleppo. Primarily a salt flat, it becomes a lake during the rainy season when it fills with water. It is not connected to any major river or freshwater lake.

Finally, it should be highlighted that these “two seas” appear to have been well known to the listeners of the preaching more or less transcribed in the Quran. Those to whom it is addressed eat fresh fish or shellfish from these two bodies of water (a saltwater sea and a freshwater lake) and see the boats that sail on them.

Q35:12 – “And not alike are the two bodies of water. One is fresh and sweet, palatable for drinking, and one is salty and bitter. And from each you eat tender meat and extract ornaments which you wear, and you see the ships plowing through [them] that you might seek of his [God] bounty; and perhaps you will be grateful.”

In the 7th-century Middle East, such a configuration of a freshwater lake near a saltwater sea is not found in Arabia or Mesopotamia (unless one considers the Shatt al-Arab—the shared estuary of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers flowing into the Persian Gulf—to be a “sea”). This configuration would therefore point to Syria, with Lake Homs (which may also be referenced in Q95:1, possibly alluding to the “Mount of Figs”, an island emerging from this lake), or, less likely, to Galilee with Lake Tiberias.

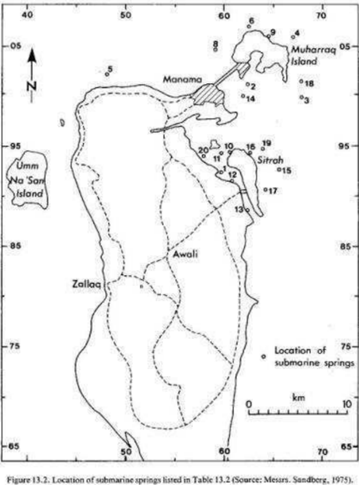

Another interpretation may also be considered by taking into account the remarkable geological phenomenon of Bahrain’s springs. The archipelago has abundant underground freshwater resources (a water table), to the extent that freshwater aquifers actually emerge on certain beaches, mixing their fresh water with the salty sea water. Some even surface on the sea floor (submarine springs): one can dive into the salty sea and encounter freshwater at depth, or even draw fresh water from the sea while aboard a boat. Ultimately, the fresh water mixes with the salt water, but the presence of fresh water in the middle of the sea remains an astonishing phenomenon—one that is also evoked in Mesopotamian myths[7].

Bahrain has also been known since antiquity for its lush vegetation, fishing activities, shellfish, and pearl production—both in the salty sea waters and in the

“marine” fresh waters fed by these aquifers. Pliny the Elder referred to the island in his writings for its pearl fishing[8]. Jan Van Reeth thus spontaneously identifies

the “ornaments” mentioned in 35:12 as the pearls fished in Bahrain[9].

(Messer, Sandberg 1975)

Furthermore, it is possible that Bahrain derives its Arabic name from this very phenomenon—al Bahrayn, meaning “the two seas” or “the two bodies of water.” Notably, this is precisely the expression used in the Qur’an.

These three correspondences with the Qur’anic text lend a certain plausibility to the hypothesis that the latter may be referring to the Bahraini phenomenon in the verses we have cited. However, it remains difficult to identify in Bahrain’s geography the “barrier” and “prohibiting partition”mentioned in the verses. Likewise, one does not observe boats sailing on a body of fresh water there, as might be implied by the passage: “you see the ships plowing through [the two seas]…” (Q 35:12).

Here again, it seems challenging to situate the context of the preaching reflected in these verses in the region of Mecca or Medina—despite Islamic tradition attributing the revelation of these verses to the Meccan period of the Prophet of Islam. The Hijaz, in fact, lies on the opposite side of the Arabian Peninsula, along its western coast bordering the Red Sea, approximately 1,200 kilometers from Bahrain.

These locations are so far from Mecca or Medina that it seems unlikely common Meccans or Medinans listening to the Quranic teachings (as is suggested in the Islamic narrative) would be familiar with them, let alone eat fresh fish from these “seas” or see the ships sailing on them. This suggests the possibility that some parts of the Quran (at least) may have been preached much farther north than the traditional Islamic narrative indicates–possibly in Syria or even around Bahrain.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqCj12vSg74

[2] See Maurice Bucaille, La Bible, le Coran et la Science : Les Écritures Saintes examinées à la lumière des connaissances modernes, Seghers 1976.

[3] al-bahrayn (البحرين — (a dual plural form — means “the two seas” or “the two bodies of water,” “the two expanses of water.” The expression appears five times in the Qur’an (25:53; 27:61; 35:12; 55:19), all of which directly relate to the subject of this article and are examined here. It also occurs in 18:60, where it refers to “the junction of the two seas” in the context of a para-biblical narrative about Moses

[4] As proposed in Quran, Saint Murad translation, PDF edition, p. 394 (“English only” edition)

[5] Q35:12 – “And not alike are the two bodies of water. One is fresh and sweet, palatable for drinking, and one is salty and bitter. And from each you eat tender meat and extract ornaments which you wear, and you see the ships plowing through [them] that you might seek of his [God] bounty; and perhaps you will be grateful.”

Q55:22 – “From both of them [the two seas mentioned in 55 :19] emerge pearl and coral.”

[6] See Patricia Crone, “How did the Quranic pagans make a living?” in Bulletin of the SOAS, Vol. 68, 3, 2005, for a more detailed analysis on fishing and sailing in the Quran.

[7] Cf. Anna Maria Kotarba-Morley, Mike Morley & Robert Carter, Freshwater Submarine Springs of Bahrain: Threatened Heritage, Alexandria University & Oxford Brookes University – https://www.academia.edu/9259603/Freshwater_Submarine_Springs_of_Bahrain_Threatened_Heritage

See also the explanations provided by the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities: https://culture.gov.bh/en/events/AnnualFestivalsandEvents/HeritageFestival/HeritageFestival2017/EternalSprings/

[8] Natural History, book VI, chapter 32 ; Pliny mentions that Tylos (the Greek name for the island of Bahrain, the main island of the archipelago) is “very famous for the abundance of pearls.”

[9] Jan Van Reeth, « Sourate 35 al-fatir (le créateur) », in G. Dye & M. A. Amir-Moezzi (dir.), Le Coran des Historiens, Le Cerf, Paris, 2019, t. 2b, pp.1175-1176

SUPPORT MY WORK

(click on button or image)

Leave a comment